The walk from the neurosurgery unit to the nursing station was long. The heels of her sandals went tick-tick on the antiseptic-smelling floor. As her legs moved, her hands tied her curly hair into a bun. The day was tiring, and her duty hours had ended. Time to go home. Maybe she could meet him.

The changing room was dark. Outside, the sun was pulling up its last rays as a sheet of black quickly covered the sky. She entered the locker room and shut the door behind her, not latching it. While unwinding her maroon saree tucked into the petticoat, she heard something fall outside. She called out, but no reply. She continued undressing.

Just as she was about to release the knot of her petticoat, the door opened, startling her. He stood there—not the man she intended to meet.

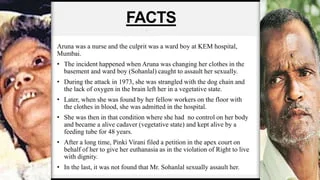

Though I’m a creative writer and take pride in creating visual imagery for my readers, what happened on the evening of November 27, 1973, chills me to the bone. I feel incapacitated when trying to narrate the horror that took place in the nursing station of KEM Hospital in Mumbai, long before I was born. For those unaware of this atrocity, I can summarize it briefly: Aruna Shanbaug, a 24-year-old nurse at KEM Hospital, was sodomized, robbed, and strangled with a dog chain by Sohanlal Walmiki, a sweeper at the hospital. She was found by a cleaner the next morning, left in a vegetative state that lasted for 43 years.

That’s it. I cannot bring myself to describe the horrors of that brutal attack. Newspaper quotes help me stay emotionally balanced while writing this piece.

My First Encounter With Aruna

In 2009, I was a final-year medical student, a young intern ready to wage war against disease. I participated in an intercollegiate fest at KEM Hospital, and the debate topic was Passive Euthanasia—A Curse or Boon. My research for the debate led me to Aruna’s story. Pinki Virani, author and journalist, had petitioned the Supreme Court to allow passive euthanasia for Aruna, who had been in a vegetative state for 36 years. Through media reports, I was shocked to learn how the rapist (it wasn’t called rape because Walmiki sodomized her while she was menstruating) walked free after only seven years of imprisonment, as he neither committed rape nor murder. Aruna lived for 43 years to tell her silent tale.

My Bond With Aruna

I won the debate, arguing in favor of passive euthanasia, but Pinki Virani lost her case, and the Nurses’ Union at KEM Hospital triumphed. Intrigued by the judgment, I read Virani’s book Aruna’s Story and discovered more about the case. I learned about the aspiring Aruna, who had moved from a small village in North Karnataka to Bombay to pursue nursing. She was set to marry a junior doctor when the sweeper began making unwanted advances toward her. Little did she know that these advances would turn malignant.

Despite being in a vegetative state, Aruna’s fiancé visited her for ten years before familial pressure led him to marry someone else. But the real question remained—who paid for Aruna’s care during her 43 years in the hospital?

A Tale Of Sisterhood

There’s a reason nurses are called “sisters.” The nurses at KEM Hospital justified this title by caring for Aruna and ensuring no government organization interfered. Her family, due to financial constraints, had given up on her, but the nurses paid for her bed, food, and medicines. Whenever a new nurse joined, she was introduced to Aruna and expected to serve her with love and respect.

Between 1973 and 2009, an unidentified person attempted to murder the paralyzed Aruna. Since then, the nursing unit became more protective, refusing external support or contact. They celebrated her birthdays, brought flowers, and kept her room locked after every visit. These women, often viewed as pragmatic, showed that wildflowers could indeed be fragrant.

One Woman Against The System

While the nurses tended to their friend, Pinki Virani fought the judicial system to allow Aruna to pass on peacefully. She argued that Aruna, deaf, dumb, and blind, was incapable of sensation except taste and smell. Virani advocated for the right to die with dignity. Though she lost the case, passive euthanasia was later legalized in India—Aruna’s gift to terminally ill patients.

Whether the nurses were Aruna’s true sakhis or Virani her best advocate is debatable. What I’ve learned from following this case is that hope comes in many forms, even in death. Women stand by each other, even in death.

Throughout her 43 years in a vegetative state, Aruna never developed a single bedsore.

India will miss such camaraderie.

Editor’s Note : This article is one of the entries for #TheShe Contest..

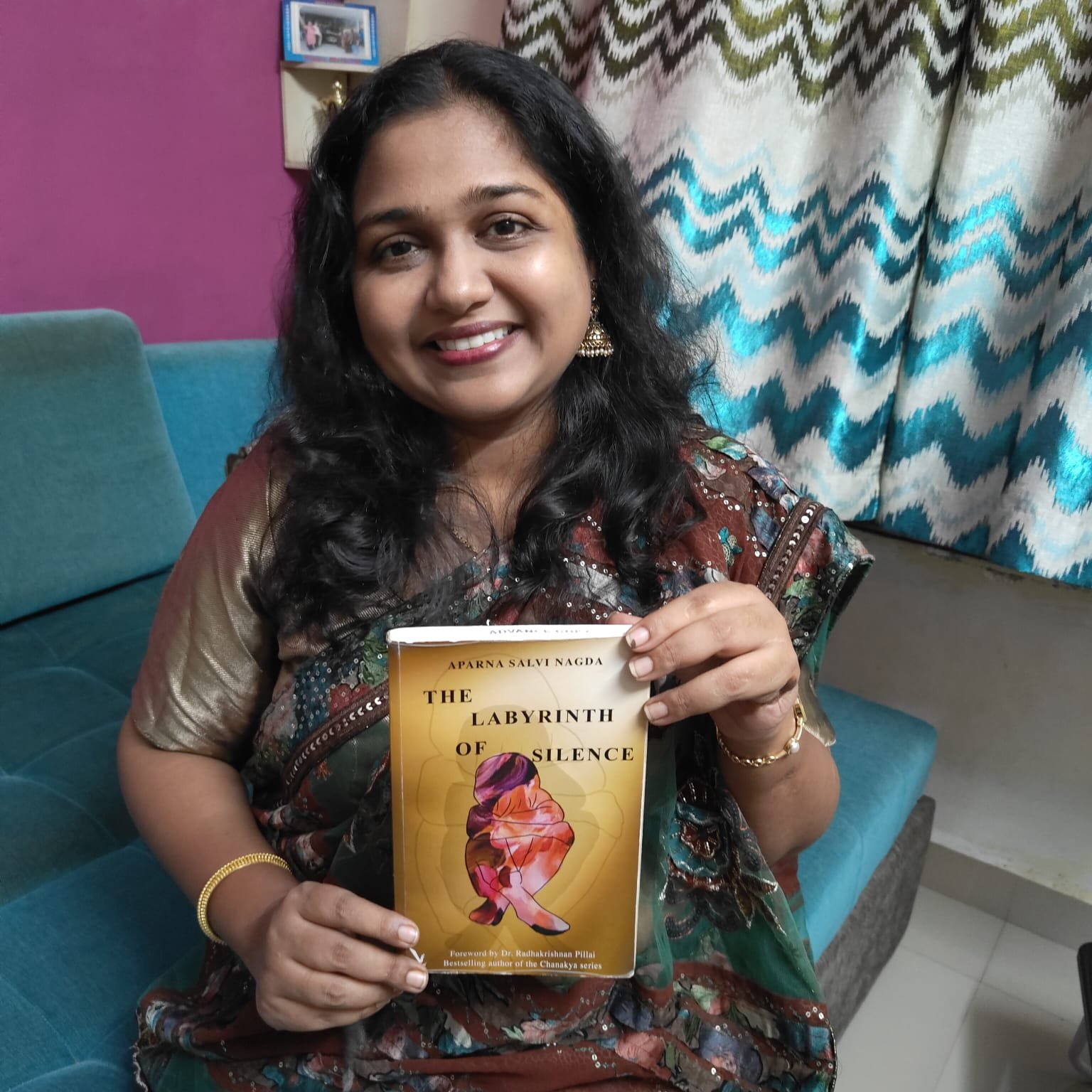

Aparna Salvi Nagda

Dr. Aparna Salvi Nagda is a consulting homeopath by profession and writer by passion. The Labyrinth Of Silence is her first full-length novel while previously she published Not So Grave, a novella, on Kindle. You can reach out to her at aparnanagda04@gmail.com

One Response

I got goosebumps and I am in tears. Indeed women stand by each other, till death. Thank you for writing this Aparna.

As a teenager I had watched Guzaarish, since then I am in favour of euthanasia. This post of you has helped me believe strongly in the same.