A lawyer, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, was entrusted with the task of drawing his pen through the map of British India. He had never set foot in the Indian subcontinent. On paper, Radcliffe made a clean division, neatly creating two separate dominions, but on the ground, it was irrevocably messy. The Radcliffe Line not only demarcated the borders of two nations but also deeply scarred the psyche of millions of people who suffered sudden displacement. Yet, displaying enormous grit, particularly the women, they rose from the ashes like a phoenix and built a new life in an unfamiliar land. They left the security of the inner quarters in search of a livelihood to supplement their family income, all while ignoring the taunts and ostracization for being a “colony girl.” After 77 years of independence, let us celebrate the women who changed the economic, social, and political landscape of West Bengal and the country and carved out their future.

Refugees In Independent India

The women of erstwhile East Bengal had left behind their ancestral homes, the familiar topography, their friends, and extended families—in short, their lives were upended as they trudged toward an uncertain future. The road was lined with violence and trauma. Upon their arrival in the new country, a new identity—Refugee—was slapped upon them. Their new homes were cramped spaces in refugee camps. The displacement of millions of people took place on both the Western and Eastern fronts. However, while the exodus from the West occurred all at once in 1947, on the Eastern front, it was a continuous trickle from Independence until the Bangladesh War of 1971. The travails of the refugees were well-documented in the West, but in the East, the continuous trickle of refugees from the borders quietly slipped out of public memory and settled into oblivion.

However, the trauma of Partition left a lasting impression in Bengali literature—novels, autobiographies, short stories, and, of course, films.

Catalyst For Social Change

Yet, when there is cynicism about what we have achieved in these long 77 years, we must remember the resilience displayed by this generation of refugees, particularly the womenfolk, who managed to find their feet and forge a new identity once again in a new and unfamiliar land.

Perhaps we, as women, should celebrate the grit and determination of our mothers and aunts who not only managed to shrug off the lowly ‘refugee’ status but also emerged from the safety of the inner quarters even to share the workspace with men.

The East Bengali women were not just victims of circumstances; they triumphed, overcoming the trauma. They changed the social reality of West Bengal, inspiring other women to come out into the public sphere. However, their domestic roles were not cut short but instead expanded to include economic, social, and even political responsibilities. Their jobs ranged from teachers, nurses, office staff, and actresses to mill workers and bidi workers. Many educated, middle-class women found employment as teachers and headmistresses of schools in West Bengal. The Partition and subsequent displacement required the establishment of many schools and colleges, and gradually, educated women found jobs as teachers in these educational institutions.

Organizations like Nari Seva Sangha, which worked among refugee women, provided vocational training, and the women joined the workforce in factories like Bengal Lamp.

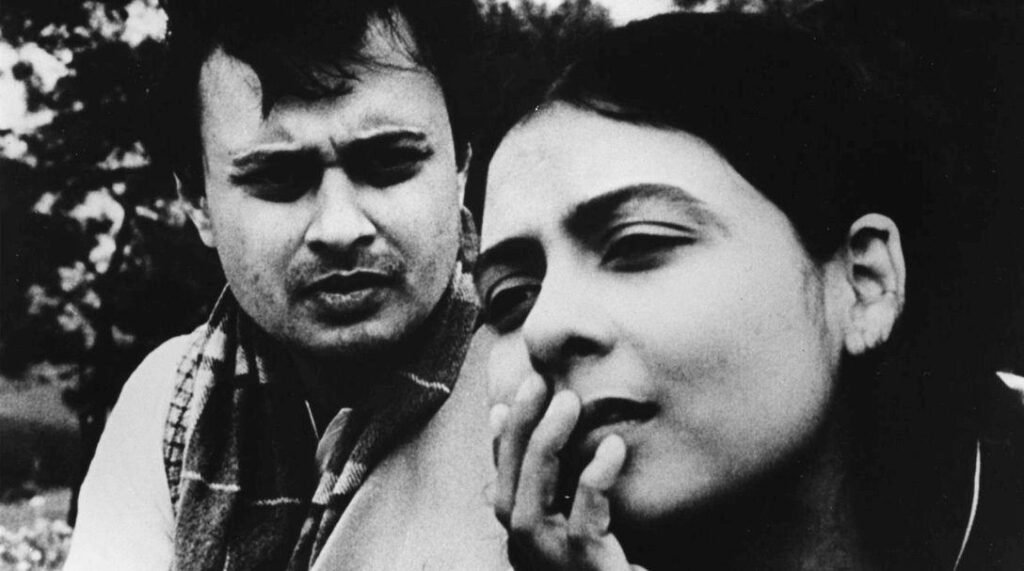

Often, they were the sole earning members of large families. Their teachers’ salaries were not enough and had to be supplemented with tuition. The protagonist, Nita, in Ritwik Ghatak’s classic film Meghe Dhaka Tara, was the sole breadwinner of the large refugee family, while her elder brother pursued his craft—singing. Mahanagar, a cult film on the changing social mores of Calcutta by the maestro Satyajit Ray, revolved around Arati, a housewife who takes up a job to supplement the family income. Arati was played by actress Madhabi Mukherjee, a refugee woman who went on to become one of the leading stars of Bengali cinema, working with almost all noted directors.

Struggle For Rights

Economic independence paved the way for their social and political emancipation as well.

With the population doubling in the truncated state of West Bengal, resources were in short supply. The refugees had to fight for every grain of rice and inch of space in the cramped quarters, and the women fought shoulder to shoulder with the men. The political roles were actually dictated by their circumstances, as a large number of refugees had settled in colonies established through ‘jabardakhal’ (squatting), where amenities were in short supply and landlords hired hoodlums to evict them. Even those who were fortunate enough to afford rented quarters experienced a life qualitatively inferior to that of the lush green countryside of East Bengal. The women became political workers, particularly joining leftist parties, as they fought for the rights of women—government jobs, grants for marriages, and the passing of a bill giving equal rights to Hindu women.

Indomitable Will

The women also carried on their traditional role of preserving their cultural heritage.

The mothers, despite limited means, continued the tradition of preparing special delicacies or performing rituals, which were then taught to the daughters and daughters-in-law with great care and affection. The East Bengali women also suffered prejudices and biases from the local population, who looked down upon them, branding them as sassy and even of loose morals. Marriages between families hailing from either side of Bengal were frowned upon, and even if there was a wedding, the girl was accepted only grudgingly. A large number of women even chose to remain spinsters, opting to bring up their siblings instead of having their own families.

Perhaps the poignant cries of “Dada, ami bachte chai” (I want to live), immortalized by Supriya Chowdhury in Meghe Dhaka Tara, best sum up the indomitable will to fight and live among the ‘refugee’ women.

By Anindita Chowdhury

Anindita Chowdhury is a special correspondent of the English daily, The Statesman. She is based in Hyderabad. Apart from reporting, she writes short stories and essays with special focus on history, particularly the social and cultural aspects of the bygone era. She can be contacted at aninditasmail@gmail.com

Facebook Comments