Sankranti has always been a favourite festival of mine. There were grand celebrations on both sides of my family, maternal and paternal. And both were in stark contrast.

The progressive matriarch

At the Asansol house (where my maternal side of the family lived), the kitchen was not part of the house. It was a single-storeyed, two-roomed structure. With a narrow strip of verandah encircling the kitchen and equipped with a huge clay oven, Sankranti was celebrated with grandeur. Dadima, the matriarch, would sit there, serving everyone Sankranti delicacies. She would initiate the process and then pass it on to the cook, who churned them out. We would sit on the floor and wait for the ‘pithe-pulis’ to be served. Everyone in the family, including the women, men, and children, would try their hands on the dough. The tradition continued as long as Dadima was hale and hearty.

The rigid patriarchal joint family

In Burdwan – the paternal side, the scenario was different. Flying kites, a house full of guests, and an abundant supply of pithe and adda were the themes. My mother along with other women would be in the kitchen downstairs, making the delicacies. It was a joint family, and invitations would be sent out to many people. Since my grandfather was an illustrious doctor, an invitation to the Sens was a prestigious affair. Guests even arrived unannounced. Imagine how prepared the women had to be with the food!

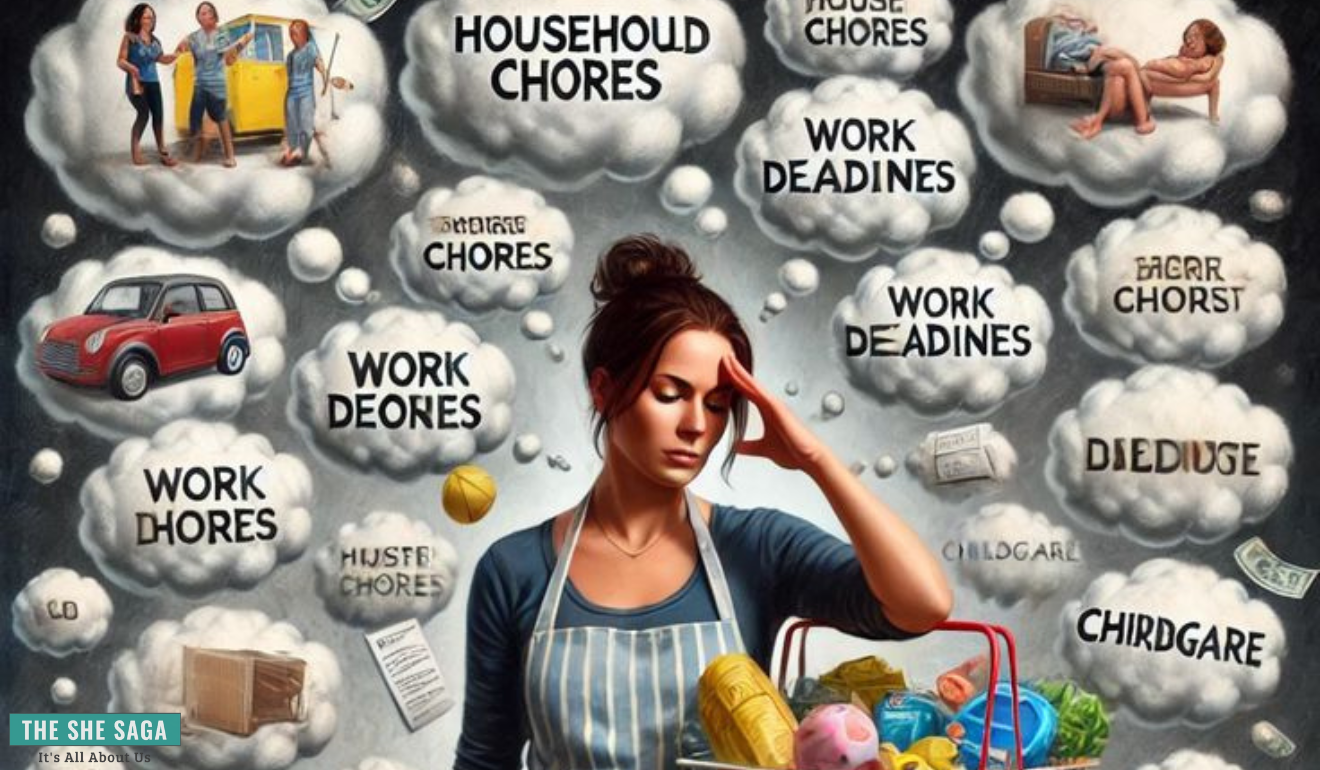

Invisible labour

It was a three-story house where the women woke up in the wee hours of the morning and slogged till night while the men entertained guests, relished the food, and flew kites on the terrace. Little girls and young women were entrusted with the task of ferrying the huge bell-metal thaalis laden with delicacies to the terrace. Sometimes, when the demand exceeded supply and the young feet found it hard to cope, Ma herself would bring them up. Her head covered with the pallu (which was a rare sight) was the norm.

Toil of tireless hands

The images have remained firmly ingrained in my mind. I noticed that at every festival, while the men entertained guests, ate, and drank, it was always the women who toiled hard. Mind you, it was not a one-day affair. Pithe and puli making is a tedious task where the ingredients have to be sourced in advance and kept ready for the process to begin in the early morning of Sankranti. In those days, the flour used to make the delicacies had to be ground at home. Who else but the women did it? It was a backbreaking task, and they embarked on it days in advance. Besides the rituals that had to be followed on a cold Sankranti morning, these women woke up at an unearthly hour and sat the whole day beside the oven, cooking.

A bitter truth

The guests enjoyed the banter and the food, and they thanked the host. But the women? They remained invisible. No appreciation or token of acknowledgement was given to them. Only young girls of marriageable age were allowed to participate on the terrace. If they remained invisible, how would they find a match?

Embracing choice

Thankfully, we visited Burdwan on special occasions. Ma escaped the drudgeries and the unfairness. In her household, she chose to bring us up on her terms. Ma tweaked the rituals to suit her lifestyle. If she wished, she invited people to Sankranti. If she didn’t feel like it, she took it easy; it was just the five of us! And they were private, enjoyable occasions. My parents knew how to make these occasions memorable.

They taught us important lessons. The right to exercise one’s choice. The will to live freely. And the biggest of all is that a festival is for everyone. It can be enjoyed when every member of the family pitches in to help.

Breaking the mould

Sankranti today is a matter of choice for us. If I am not well, there are no obligations for me to make the delicacies. It’s much colder this year. We cannot be expected to take a head bath early in the morning, right? So we wait for the sun to shine brightly, switch on the geyser, and take a leisurely bath. There are not too many rituals that we follow. Offering delicacies to our household deity, lighting agarbattis, and a short prayer thanking the almighty for his blessings is what we do; temple visits are not compulsory.

If one of us is travelling, we ensure that we celebrate on a day when everyone is home, on a day when the workday is lower, or over the weekend when we have time to hang loose.

And in my family, it’s not the woman who does it all. The husband is an expert and dons the chef’s cap on these special occasions; we are just his assistants, obeying every command of his. Today, all of us take an active interest in our festivals, for we know it is an enjoyable experience.

It’s time we do away with the age-old norms, smash the patriarchy, and ensure that every member of the family gets involved. Only then can we enjoy our festivals. It is only then that our festivals will no longer weigh heavily on us, and our children will be encouraged to carry on the legacy!

(Cartoonist -Mali’s)

Facebook Comments