I guess I was already a little in love with Lucknow even before I landed at its airport. My love and fondness for the city were fostered by none other than Satyajit Ray, as one of his early detective stories, ‘Badshahi Angti’, was set in Lucknow. And it was through Ray’s eyes (and his film ‘Shatranj ki Khilari’) that I had discovered another aficionado of Lucknow – the deposed Nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah, a much-reviled man in history. It was Wajid Ali Shah who had transformed the colonial upstart Calcutta into a city of palaces, culture, music and dance in his soul’s quest to find another Lucknow in this marshy port city. Although the British razed the majority of his palaces after his death, his fingerprints on the city’s culture and gastronomy were indelible. I was always curious to see the city that had shaped him and follow the trail left behind by Ray’s fictional private detective Feluda and his cousin cum sidekick Topshe.

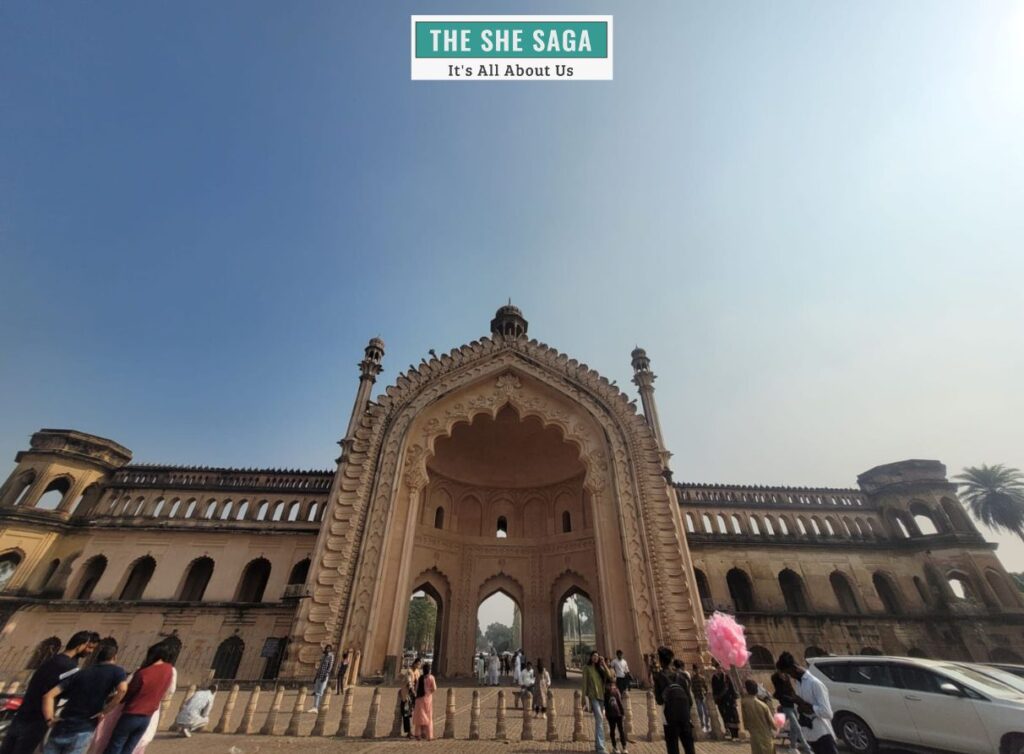

For a history buff who revels more in ruins than modern concrete and glass buildings, old Lucknow can be charming. Our journey began predictably from the majestic gateway, Rumi Darwaza, built almost two and a half centuries ago, but still retains its architectural beauty. Interestingly, most of the Nawabi era buildings and monuments have a pair of fish or “Mahi Maratib” engraved on them as the official emblem of the State of Awadh. The story goes that a pair of fish leapt on the lap of the first Nawab of Awadh, Saadat Khan, while he was travelling to Lucknow from Farrukhabad by boat, which he considered to be a good omen and promptly adopted as his official emblem. Each of the historic buildings, the Chota Imambara, the Bada Imambara, the incomplete observatory Satkhanda or the Hussainibad clock tower have their own tale to tell. But the one about the gargantuan Bada Imambara, built by Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula, undoubtedly, turned out to be the most interesting.

The vast size of the Imambara, along with a mosque and a baoli or stepwell in its premises, is one to reckon with, however, this architectural marvel allowed the Nawab to design one of the first food-for-work projects to help his subjects when a devastating famine hit the kingdom. The common subjects would be hired as labourers for the construction work, and in the darkness of the night, another group of subjects – the nobles who were too embarrassed to work during the day would demolish whatever the plebians had been built earlier. The food would also come from the Nawab’s kitchen and the khansamas would make a one-pot dish of rice and meat for the labourers and put it on the dum for hours and lo! you had the famed biryani of Lucknow. Of course, when it found a permanent place in the kitchens of the Nawab, exotic spices were added to it. The chefs who accompanied the exiled Wajid Ali Shah brought it to Calcutta, but the city added its own exotic vegetable – the potato, which was introduced to India by the Portuguese. The exiled Nawab was given a hefty pension by the British and hence was never reduced to penury, as many would like us to believe.

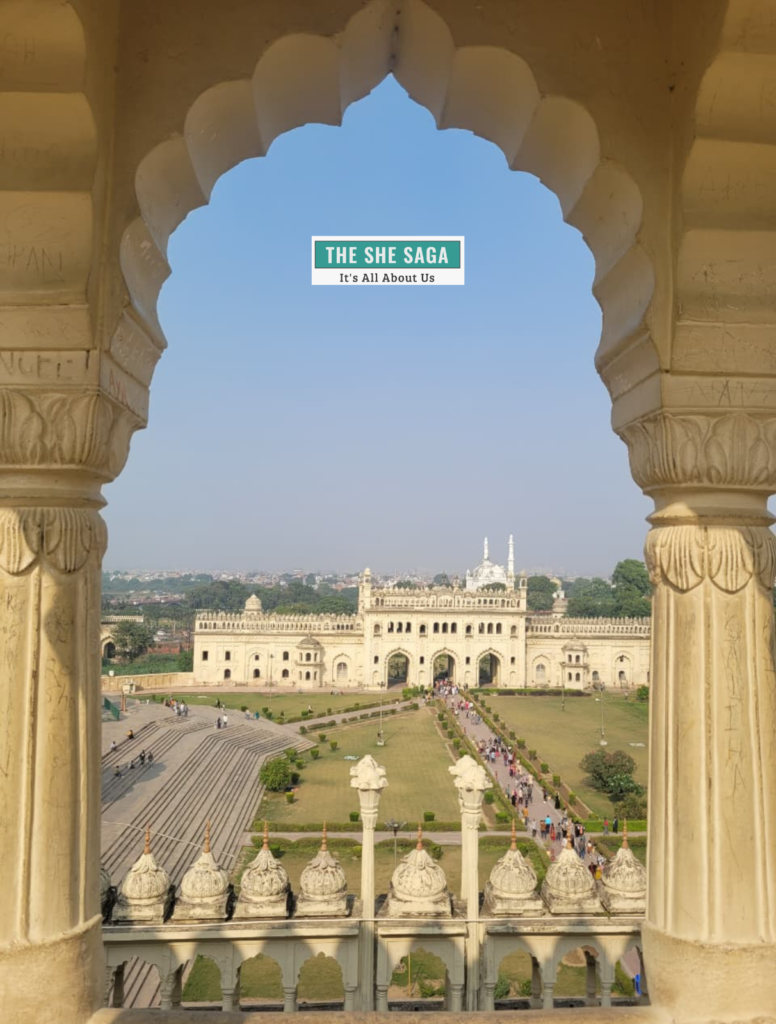

The much-famed labyrinth Bhool Bhulaiya is neither a place for the faint-hearted and the weak-kneed, but an architectural marvel to hold upright the Imambara’s vaulted roof without beams and pillars. Along with myriad passages and doorways, it was the peephole windows that allowed those inside to keep an eye on outsiders approaching the entrance without revealing their own positions. Once you reach the vast terrace, you get a bird’s eye view of the monuments around, including the beautiful Rumi Darwaza and Teele Wali Masjid.

Our history textbooks only attributed a paragraph or two to the long Siege of Lucknow between the British and the Indian soldiers during the Revolt of 1857, but the heavy shelling that ravaged the walls of the various buildings of the Residency is ample testimony of the fierce fighting between the two sides. The small museum has documents of the communication between the British commander and the headquarters in Kolkata. Even if you are not a history buff, the vast gardens of the Residency are like an oasis of peace with flocks of parrots and squirrels as the permanent residents. Close to the Residency, the General Wali Kothi on the banks of the River Gomti is another architecturally beautiful building, taken over by the rebels during the rebellion. After putting down the revolt, the British preserved the ruined buildings of their Residency but razed to the ground several palaces in Kaiser Bagh built by Wajid Ali Shah. Among the few that stand, the Saadat Ali Tomb complex is home to two beautiful tombs. Wajid Ali Shah, a poet, a patron of thumri and a keen Kathak dancer who composed the first Urdu opera on Rasleela of Krishna and Radha, had also built a Parikhana, an institution of fine arts. The building survives and houses the Bhatkhande Music Institute. Kaiser Bagh has fallen victim to urban sprawl. Yet, we caught a glimpse of the beautiful, mellowed yellow walls of the Mahmudabad House, where the historic Lucknow Pact of 1916 between the Congress and the Muslim League was negotiated and signed.

Apart from the Residency, the Dilkhusha Kothi, once the hunting lodge and summer palace of the Nawab, also saw plenty of action during the Rebellion. Today, only skeletal relics of the baroque-style buildings remain, though the sprawling open gardens make it popular among morning walkers. It was also the setting of Satyajit Ray’s short story “The Duel of Lucknow, one of the grandiloquent tales spun by his fictional character, Tarini Khuro. Since I could not find a reference to a duel in Lucknow, I wonder if Ray was inspired by the duel between the then Governor-General Warren Hastings and his arch-rival, Philip Francis, that took place in 1780 at Belvedere Estate over the latter’s affair with Calcutta’s great beauty, Madame Grand.

Lucknow also charms the visitors with its gastronomic delights. Imagine waking up to Nihari and Barkakhani and rabri at breakfast, galouti at lunch and more varieties of succulent kebabs like Majlishi or dum biryani at dinner. In fact, we were simultaneously on a food trail, visiting every nukkad, lane, and by lane, sampling the various kebabs, rotis, biryani, and nihari. No wonder UNESCO recently recognised its culinary heritage with the “Creative City of Gastronomy” tag. The mattha, makhan malai, basket chaats, the kaali gajar ka halwa and malai pan or gillori of Ram Ashray sweet shop are all worth a taste. And if you are passionate about handcrafted items, do spend some time looking for authentic chikankari, the smallest hand-done stitches, tracing out paisleys or other delicate designs on pastel-hued cloth.

Lucknow touches you at the very core with its gentleness and cordiality. The city’s understated vibe leaves its subtle taste not only on your palate but also soothes your soul. After the short visit, I perhaps fathom Wajid Ali Shah’s anguish better, when he had bid farewell with this composition, “Jab chod chale Lucknow nagri kahen haal ke hum par kya guzari.”

By Anindita Chowdhury

Anindita Chowdhury is a special correspondent of the English daily, The Statesman. She is based in Hyderabad. Apart from reporting, she writes short stories and essays with special focus on history, particularly the social and cultural aspects of the bygone era. She can be contacted at aninditasmail@gmail.com.